“I definitely recommend this trip. It is a fun learning experience, and the memories I have made there I will surely never forget…You also get to hear different types of opinions from your group mates on government issues.” – Josie Smith

“I definitely recommend this trip. It is a fun learning experience, and the memories I have made there I will surely never forget…You also get to hear different types of opinions from your group mates on government issues.” – Josie Smith

“I definitely recommend this trip. It is a fun learning experience, and the memories I have made there I will surely never forget…You also get to hear different types of opinions from your group mates on government issues.” – Josie Smith

“I definitely recommend this trip. It is a fun learning experience, and the memories I have made there I will surely never forget…You also get to hear different types of opinions from your group mates on government issues.” – Josie Smith

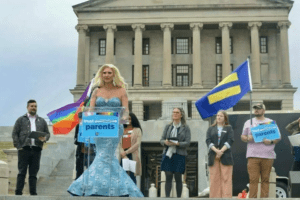

Last month, Tennessee Governor Bill Lee signed a first-of-its-kind law banning “adult cabaret entertainment” on public property or in any location where people under 18 could be present.

Senate Bill 3, commonly known as the “drag ban,” in part defines these performances as “male or female impersonators who provide entertainment that appeals to a prurient interest, or similar entertainers.”1 The law calls for first-time offenders to be charged with misdemeanors with subsequent offenses classified as felonies that could result in prison sentences of up to six years. The Republican-controlled Tennessee Senate passed the ban into law on March 2 with the intention for it to go into effect on April 1. The law was halted by a federal judge hours before it was to go into effect using a temporary restraining order, citing constitutional protections of freedom of speech.2

The drag ban has become a national conversation, with opponents of the law criticizing it for targeting the LGBTQ+ community. It follows several other issues considered by Governor Lee over the last couple of months, including prohibiting transgender Tennesseans from changing the gender listed on their driver’s license and prohibiting referrals for children to receive gender-affirming care in the state.3 Those opposed to the law are concerned that it is too vague in its definitions of what constitutes a “drag” impersonation and how to discern a location where a minor may be present. Both the American Civil Liberties Union and the Human Rights Campaign have expressed concerns that the law gives too much power to law enforcement to interpret the drag ban as they choose and potentially target transgender and gender-nonconforming entertainers performing in public.4

Members of the drag community argue that drag performances are much like any other form of entertainment. They say that just as some movies or comedy shows are appropriate for children and some are not, there are drag performances made appropriate for children and performances intended for adults. Performers are worried that authorities will not bother to discern the difference or will abuse the law in an effort to ban all drag performances.

State Senate Majority Leader Jack Johnson, a sponsor of the drag ban bill, argued on Twitter, “The bill gives confidence to parents that they can take their kids to a public or private show and will not be blindsided by a sexualized performance.”5 He continued, “We’re protecting kids and families and parents who want to be able to take their kids to public places. We’re not attacking anyone or targeting anyone.”6 While his sentiments were supported by most Republican legislators, Judge Thomas Parker—who ordered the temporary halt on the Tennessee drag ban and a Republican himself—felt the law was an overreach of government authority.

Regina Lambert Hillman, a professor of law at the University of Memphis, assured that the ban cannot prevent transgender persons from dressing as they choose in public. She explained in an essay, “You still have First Amendment protections, what that means is how a person dresses or what a person says, that does not change. The government cannot suppress speech, including expressive conduct, just because they find it offensive or they don’t like the content.”7

Though this law is the first of its kind passed, 14 other states have introduced similar legislation this year. Experts see this legislation as a coming trend that will likely cause similar conversations about whether it’s a First Amendment violation, LGBTQ+ rights, and how a law like this could be enforced. Meanwhile, the courts will be tasked with determining whether such laws are constitutional.

READ the full bill summary here.

Discussion Questions

Other Resources

Related Posts

As always, we encourage you to join the discussion with your comments or questions below.

Sources

There is a lack of public restrooms in America. It’s a problem you might only notice when you need to go. Those with chronic conditions such as gastrointestinal disorders, parents with young kids, and older Americans with weaker bladders may be most affected by this shortage, though anyone who just drank a large iced coffee can find themselves in need of—and struggling to find—a bathroom.

There is a lack of public restrooms in America. It’s a problem you might only notice when you need to go. Those with chronic conditions such as gastrointestinal disorders, parents with young kids, and older Americans with weaker bladders may be most affected by this shortage, though anyone who just drank a large iced coffee can find themselves in need of—and struggling to find—a bathroom.

A 2021 report by QS Bathrooms Supplies, a United Kingdom-based bathroom retailer, found that the United States had only eight public restrooms per 100,000 people.1 These are typically located in parks, by public transit, or in publicly accessible buildings, though they can be tough to find in times of emergency. Some people have taken it upon themselves to scope out and share locations of public toilets, like Theodora Siegel, who created a TikTok account that posts videos about free public bathrooms in New York City.2 She’s even crowdsourced an interactive Google Map with all the locations.3

The public restroom shortage means that the responsibility often falls to private businesses. When asked in 2002 about building more public restrooms, then-New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg replied, “Why? There’s enough Starbucks that’ll let you use the bathroom.”4 Though businesses, hotels, libraries, and museums have stepped up with “open-bathroom” policies to provide this public service, people may still feel obligated—or be outright required to—purchase a product or service to gain access to a toilet.5 And depending on the hours of operation, these bathrooms may not be available at certain times of day.

Public Toilets in the Past

America’s standalone public toilets date back to colonial times, when buildings had no indoor plumbing or dedicated “bathrooms” like the ones we’re used to. According to Debbie Miller, who serves as a museum curator at Independence National Historical Park in Philadelphia, these public toilets were “common and generally communal” across the colonies; there was even an “octagonal outdoor toilet” located behind Independence Hall.6

At the turn of the 20th century, leaders of the temperance movement successfully advocated for the creation of public restrooms outside saloons in the hope that they would lead men to consume less alcohol in bars that had bathrooms.7 Throughout the Great Depression, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal public works programs built over two million “sanitary privies” in parks and “comfort stations” in cities across the country.8 By the 1970s, there were over 50,000 coin-operated pay toilets in America’s urban centers.9

The rise of the automobile and decline of downtown led to the closure of many public restrooms in train stations, bus terminals, and commercial districts.10 The New York City subway had 1,676 public restrooms available in the 1940s; by 2022, that number was down to a mere 78.11 Costly upkeep and strained budgets led to the removal of many public restrooms in subsequent decades, as toilets fell victim to vandalism and neglect.12 They were seen as dark and dirty, unsanitary and unsafe.

Private and Public Solutions

Public restrooms can cost anywhere from $80,000 to $500,000 to construct, and they require daily maintenance to keep them clean and functioning.13 Chad Kaufman, president of the Public Restroom Company which manufactures restrooms, notes that while cities “might have grant funds or public funds to build things, they typically don’t have operational funds to maintain these things.”14 The often glacial pace of government action means that it could take years to select a location, approve a plan, and design and construct the facilities.

The Council of the District of Columbia in 2017 passed the Public Restroom Facilities Installation and Promotion Act, which required a number of agencies to select sites and install public restrooms.15 It also required the mayor to “establish a financial incentive program to encourage private businesses to make their restrooms available to the public for free.”16 This sort of private-public partnership has been implemented in other countries like Germany and England, where local governments pay businesses a small stipend to promote their free toilets.17

In 2008, the city of Portland, Oregon, collaborated with a private manufacturer to design and install 24-hour, single-occupancy bathrooms called the “Portland Loo.”18 They have since been installed in dozens of other cities across the United States and Canada. China’s government led a directive, dubbed the “Toilet Revolution,” which constructed nearly 70,000 publicly accessible toilets in just two years.19 And in Tokyo, restrooms are designed to be vibrant works of art with bright colors, sleek designs, and “smart glass” that provides transparency and turns opaque when occupied.20

Prioritizing Public Restrooms

From a public health perspective, sanitation is crucial to well-being. An individual’s health contributes to the health of the community and the greater common good. When businesses were shuttered during the COVID-19 pandemic, we saw just how vital their bathrooms were to the public. When people don’t have access to a toilet—or a sink to wash their hands—germs and illnesses spread. Bathrooms also keep the surrounding areas of a community clean. They guarantee dignity to people who must meet their basic bodily needs. It can be humiliating to need the bathroom and not be able to go. People might risk arrest for public urination or end up soiling themselves because they couldn’t find one in time.

America’s restrooms should be easy to find, easy to use, safe, and comfortable. As communities improve their public spaces and upgrade their infrastructure, they should consider solutions that make sure their restrooms are accessible to all—regardless of disability, gender, gender identity, age, or socioeconomic status.

Discussion Questions

As always, we encourage you to join the discussion with your comments or questions below.

Sources

On March 23, 2023, the House Committee on Energy and Commerce held a hearing as part of an ongoing review of TikTok and its connections to the Chinese government. TikTok CEO Shou Chew was the focus of the hearing and took questions from members of Congress on a wide range of topics, including the ways TikTok gathers and secures user data and the access the ruling party of China, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), has to that data.1

Currently, there is bipartisan support for enacting a ban on TikTok in the United States. The federal government and dozens of state governments have already enacted various policies banning the social media app in official spaces, on official computers, and/or in employees’ personal capacity.2 However, the ban currently gathering support in Congress would make the app unusable by private citizens regardless of their government status, employment, or age. Such an outright ban on social media extended to individual citizens would be unprecedented in the United States and has generated significant controversy.3

READ MORE: For an in-depth look at whether or not Congress should ban TikTok, subscribers can access a new Close Up Current Issue on the topic!

Should TikTok be Banned?

Bipartisan support is not often found in today’s Congress, particularly on far-reaching legislation. Despite Chew’s insistence during his testimony that TikTok has never provided user data to the CCP and would not do so if asked, Democrats and Republicans in Congress remain highly concerned over the security threat they believe TikTok represents.4

At the heart of their concern is the close relationship that major Chinese corporations, including TikTok’s parent company ByteDance, have to maintain with the CCP in order to thrive in China. They argue that despite the assurances of CEOs like Chew, the Chinese government ultimately has the power to access any information Chinese companies retain and can easily compel them to release that data.5

Lawmakers and law enforcement agencies have also cited TikTok as a potential source of pro-China and/or anti-U.S. manipulation, disinformation, and propaganda.6 In an effort to address some of these concerns and prevent a ban, TikTok has proposed Project Texas—a $1 billion plan to ensure that all U.S. data is stored outside of China.7 For many lawmakers, this proposal does not do enough to guarantee that data is protected and that the CCP cannot utilize that data to undermine U.S. interests and national security.

During the hearing, Representative Dan Crenshaw (R-Texas) addressed spectators directly by saying, “I want to say this to all the teenagers out there, and TikTok influencers who think we’re just old and out of touch. … You may not care that your data is being accessed now, but you will be one day.”8

Why Keep TikTok?

Currently, more than 150 million Americans are on TikTok, making it one of the most popular social media apps in the country, particularly among teenagers and young adults. The average TikTok user in the United States spends over 90 minutes on the app per day, opening the app no less than eight times during the day.9 In response to the proposed ban, some users have joined together to voice their opposition and the hearing itself became a focus of users’ objections. Many users argued that the hearing only underscored how out of touch lawmakers are with the realities of technology and social media.

Recently, Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) took to TikTok for the first time to announce her opposition to the ban. “They say because of this egregious amount of data harvesting, we should ban this app,” she said. “However, that doesn’t really address the core of the issue.”10 The core of the issue she alluded to is one cited by many of those opposed to the ban. Beyond the fact that TikTok is simply a popular app that users enjoy, some argue that the data-harvesting practices that lawmakers are concerned about are standard to nearly all social media and internet apps. Critics have agreed that data-harvesting and a lack of data privacy are major issues in the United States, but many say a ban on TikTok would do virtually nothing to substantively address those issues.11

For many, a potential TikTok ban also raises broad questions about First Amendment rights—particularly free speech and free expression. Opponents of a TikTok ban question whether the government has any business policing the private activities of private citizens regardless of motive. Some feel that those who have concerns about TikTok’s data privacy practices have the option of not using the app and that the choice of whether to do so should be left to the individual. They argue that while the government may reserve the right to make its own data policies for its employees, it should not be allowed to do the same for private citizens. 12

Discussion Questions

Related Posts

Fallout and Consequences Part 2: Free Speech and Censorship

As always, we encourage you to join the discussion with your comments or questions below.

Sources

12News travelled alongside a group of Arizona high school students who visited the nation’s capitol to learn necessary skills in government.

12News travelled alongside a group of Arizona high school students who visited the nation’s capitol to learn necessary skills in government.

Arlington, VA—The Close Up Foundation is pleased to announce that it has named Mia Charity as its new president and Stephanie Stargell as chief financial and operating officer, effective March 23, 2023.

Arlington, VA—The Close Up Foundation is pleased to announce that it has named Mia Charity as its new president and Stephanie Stargell as chief financial and operating officer, effective March 23, 2023.

On February 18, the Carter Center released a statement saying that former President Jimmy Carter had opted to spend “his remaining time at home” following a number of hospital stays and declining health.1 News of the 98-year-old former president’s condition has brought an outpouring of support and renewed attention to his life and legacy as the 39th president of the United States. President Carter’s “Crisis of Confidence” speech is perhaps his most famous, and its words are still relevant for our country today.2

On February 18, the Carter Center released a statement saying that former President Jimmy Carter had opted to spend “his remaining time at home” following a number of hospital stays and declining health.1 News of the 98-year-old former president’s condition has brought an outpouring of support and renewed attention to his life and legacy as the 39th president of the United States. President Carter’s “Crisis of Confidence” speech is perhaps his most famous, and its words are still relevant for our country today.2

President Carter delivered this speech, often referred to as his “Malaise Speech,” on July 15, 1979, while the country was in the midst of an energy crisis.3 After spending several days listening to the concerns of everyday Americans, he concluded that America as a whole suffered from what he called a “crisis of confidence.” This, he said, was a “fundamental threat to American democracy.”4

The threat is nearly invisible in ordinary ways. It is a crisis of confidence. It is a crisis that strikes at the very heart and soul and spirit of our national will. We can see this crisis in the growing doubt about the meaning of our own lives and in the loss of a unity of purpose for our nation. The erosion of our confidence in the future is threatening to destroy the social and the political fabric of America.5

President Carter went on to explain that people had lost faith in their government, in each other, and in their own abilities as citizens to shape their democracy. He recognized the disconnect between the federal government and everyday communities. People felt like their government was not working for them. They grew tired of inaction, inefficiency, partisanship, and the unwillingness of elected officials to compromise for the sake of the common good. Americans, in his eyes, were skeptical of the future and doubted the progress we had made as a nation.

For the first time in the history of our country, a majority of our people believe that the next five years will be worse than the past five years. Two-thirds of our people do not even vote. The productivity of American workers is actually dropping, and the willingness of Americans to save for the future has fallen below that of all other people in the Western world.6

These problems persist in our current political climate. According to a recent NBC News poll from the summer of 2022, three quarters of voters said that the country is “headed in the wrong direction,” with 58 percent also adding that “America’s best years are behind it.”7 And although the 2020 election saw record voter turnout, one third of eligible voters still did not vote.8 Trust in government has been eroding for decades. A May 2022 Pew Research poll found that only 20 percent of Americans believed they could trust the government to do what is right “always or most of the time.”9 This is down from 30 percent who said the same at the time of President Carter’s speech.10

Though the main focus of President Carter’s speech was the energy crisis, he was speaking to a country that had experienced political shock and cynicism. It had seen the assassinations of political and civil rights leaders. It had grown disillusioned with the Vietnam War. There was a widespread feeling of distrust in government institutions and elected officials post-Watergate, and people were hurting financially due to stagflation (high inflation, high unemployment, and slow economic growth).

Americans today face their own similar and unique challenges: the COVID-19 pandemic, climate change, high inflation, misinformation, and issues of civil rights and racial justice, among others. Lies about the legitimacy of elections led to an attack on the Capitol and continue to saturate our national discourse. Hyperpartisanship has distorted the way we see each other, and a breakdown in basic levels of decency among individuals and political leaders has furthered the divide between “us” and “them.”

President Carter urged Americans to trust in each other and once again find common purpose in order to overcome this ongoing crisis. To reunite the country, it was imperative to restore our “American values.”11 This would take time and effort on behalf of all of us. “Little by little we can and we must rebuild our confidence. We can spend until we empty our treasuries, and we may summon all the wonders of science,” he concluded. “But we can succeed only if we tap our greatest resources—America’s people, America’s values, and America’s confidence.”12

Discussion Questions

Other Resources

As always, we encourage you to join the discussion with your comments or questions below.

Sources

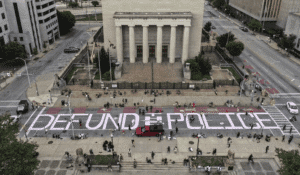

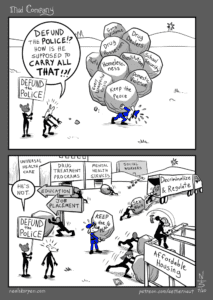

Following the 2020 murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin, a call by activists to “defund the police” achieved national attention. Supporters of defunding the police have argued that—at least some of—the billions of dollars spent on policing each year could be better used by investing in educational, recreational, and mental health programs, among others, in an effort to reduce crime and increase community well-being more generally. With the release of footage showing multiple officers pepper-spraying, kicking, and punching Tyre Nichols—leading to his death three days later—questions of whether and how to reduce police budgets have been brought back into the national conversation.1

Following the 2020 murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin, a call by activists to “defund the police” achieved national attention. Supporters of defunding the police have argued that—at least some of—the billions of dollars spent on policing each year could be better used by investing in educational, recreational, and mental health programs, among others, in an effort to reduce crime and increase community well-being more generally. With the release of footage showing multiple officers pepper-spraying, kicking, and punching Tyre Nichols—leading to his death three days later—questions of whether and how to reduce police budgets have been brought back into the national conversation.1

In order to understand this issue, it is important to define what defunding the police means and what it doesn’t mean. Responding to the deaths of five Dallas police officers in a 2016 mass shooting, Dallas Police Chief David Brown said, “We’re asking cops to do too much in this country. … Every societal failure, we put it off on the cops to solve. Not enough mental health funding, let the cops handle it. …Here in Dallas we got a loose dog problem; let’s have the cops chase loose dogs. Schools fail, let’s give it to the cops. … That’s too much to ask. Policing was never meant to solve all those problems.”2

This is what many activists mean when they call for the police to be defunded. Reduce the number of responsibilities we ask of the police, decrease police budgets to match the reduced size of the police force, and use the diverted funds to invest in programs and staff who are trained to address mental health crises, struggling schools, and other social issues.

This is what many activists mean when they call for the police to be defunded. Reduce the number of responsibilities we ask of the police, decrease police budgets to match the reduced size of the police force, and use the diverted funds to invest in programs and staff who are trained to address mental health crises, struggling schools, and other social issues.

“Defund the police” does not mean “abolish the police.” It means police would have a more limited, primarily peacekeeping role. But they would not be asked to take on other roles, like those mentioned by Chief Brown.

Defunding the police is not a brand-new movement. Activists have been calling to defund the police for nearly a decade—since at least 2014, following the death of Michael Brown at the hands of police in Ferguson, Missouri—but the slogan caught on much more broadly in 2020, even being echoed by some progressive members of Congress.3 While many Democratic Party leaders worried that the slogan was “divisive,” members of the so-called “Squad,” including Representatives Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.), Ilhan Omar (D-Minn.), and Rashida Tlaib (D-Mich.), expressed support for defunding the police. They were clear that they did not want only to cut police funding, but to redirect those taxpayer dollars into other social services.4

The movement to defund the police has also garnered opposition. Opponents of the idea believe it is unwise to call for reducing the size and budgets of police forces when crime has risen in some parts of the country in recent years. Opponents argue that such a policy could actually encourage crime by reducing the capacity of police forces. As Jacqueline Helfgott, a professor of criminal justice at Seattle University, wrote, “If we defund the police, those most affected will be the poor and the marginalized. Wealthy neighborhoods will hire private security as they are already doing, and poorer neighborhoods will have to fend for themselves even more than they already have to. Delays in police response and lack of police capacity will increase fear of crime, render victims of crime helpless, and wreak havoc on communities, especially communities of color, even more so than is already the case.”5

Other political activists and commentators want to go beyond merely reducing the budgets and responsibilities of law enforcement and “abolish the police.” In an interview following Nichols’ death, police abolitionist Andrea Ritchie called for police to be phased out completely, beginning with limiting their authority to conduct certain actions, starting with traffic stops. “[I]t would require a complete restructuring of the society that we live in,” she said. “It would require us to shift our priorities from responding to every form of need, conflict, and harm with agents of violence. … And so, it does require a radical reimagination of what we understand safety to be.”6 Ritchie and other police abolitionists make the case that “safety is not produced primarily through force,” and therefore, “police don’t make us safer.”7

WATCH: “Howard Prof. Justin Hansford & Abolitionist Andrea Ritchie on Tyre Nichols & Calls for No More Police,” from Democracy Now!

Police abolitionist scholars have argued that the over-policing of Americans—disproportionately low-income people of color—has led to “the systematic mass incarceration of people of color in the United States,” most directly through the War on Drugs.8 Alex Vitale explains that, as a response to the War on Drugs, the Los Angeles Police Department “developed specialized antigang units first known as TRASH (Total Resources Against Street Hoodlums) and later sanitized [renamed] CRASH (Community Resources Against Street Hoodlums)” in the 1970s.9 These specialized police teams became the model for later elite forces, such as the Memphis Police Department’s SCORPION Unit (Street Crimes Operation to Restore Peace in Our Neighborhoods), five members of which have now been charged with the murder of Nichols.10

READ: “To Produce Safety, We Must Understand What Drives Violence,” from Common Justice

With another high-profile police killing of an unarmed Black man, Americans are once again reconsidering what safety looks like and how police fit into that picture.

Discussion Questions

Possible Extension Activities

Further Reading

Related Posts

Protests, Police Reform, and Civil Unrest

As always, we encourage you to join the discussion with your comments or questions below.

Sources

There is currently a bill in Congress, S.794 – Tax Excessive CEO Pay Act of 2021, that would increase taxes on companies on the basis of their CEO-to-worker compensation ratio. The legislation, introduced by Senator Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) and cosponsored by a host of Democrats including Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), has progressed to the Senate Committee on Finance but faces an extremely polarized Congress.

In the proposal, a ratio is ascribed to a company by dividing the CEO’s compensation by that of the median employee.1 The tax hike proposed in the Tax Excessive CEO Pay Act is gradually increased in proportion to the ratio, starting with a 0.5 percentage point increase for companies that pay their chief executive between 50 to 100 times more than their median worker. The highest tax applied is a five percentage point increase for corporations in which the CEO makes more than 500 times the typical employee. These percentage points would be added to the current corporate income tax rate of 21 percent.1

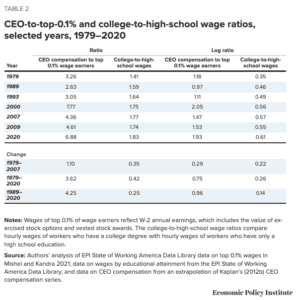

Compensation ratios vary greatly depending on specific organizations. Coca-Cola’s ratio, for example, is on the high end of the spectrum at 1,621 to 1.2. Of the top 1,000 firms, around 80 percent would be subject to higher taxes because of pay disparity.2 However, compensation can sometimes be difficult to calculate, with many CEOs receiving stock options and other forms of payment. Using data from the top 350 firms, the Economic Policy Institute (EPI) found the CEO-to-worker pay ratio to be 399 to 1 in 2021.3 This is an increase from 20 to 1 in 1965 and 58 to 1 in 1989.4 Some scholars credit this trend as contributing to growing wealth inequality in the United States. The EPI study found that from 1978 to 2019, CEO compensation expanded by 940 percent while median worker compensation grew by only 12 percent.3 The nearby chart illustrates the incongruent growth.

Arguments for the Tax Excessive CEO Pay Act

Arguing in support of the legislation, Senator Warren said, “We need to take dramatic steps to address wealth inequality in this country and discouraging massive executive payouts is a good place to start.” She added, “Corporate executives have padded their pockets while American workers, who helped generate record corporate profits, have hardly seen their wages budge.” Senator Sanders also views the current CEO-worker dynamic as inequitable and believes it is time for corporations to “pay their fair share.”5

Others argue that even if the tax does not incentivize companies to lessen the gap between CEO and worker compensation, the tax could still generate revenue that could be reinvested. A similar, but less extensive, tax in Portland, Oregon, generated $5.2 million in 2019. On a federal scale, the revenue could be used to tackle any number of issues facing America.

Arguments Against the Tax Excessive CEO Pay Act

Opponents argue that in cities like Portland that have experimented with similar taxes, the policy has not led to a dramatic lessening of CEO compensation.6 In fact, detractors insist that instead of reducing CEO pay, the policy would lead corporations to pass this new tax burden onto workers (in the form of lower wages) and consumers (in the form of higher prices).7 This ultimately hurts lower-income individuals the most.8 Others argue that the Tax Excessive CEO Pay Act would disproportionately harm specific sectors of the economy. Industries such as retail and fast food tend to rely on lower-skilled labor and could be affected more than specialized industries. Opponents worry that this disproportionate targeting could disrupt the fair and normal functioning of the economy and the global competitiveness of U.S. companies.

Discussion Questions

Related Posts

Addressing Economic Inequality: Elizabeth Warren’s Wealth Tax Proposal

As always, we encourage you to join the discussion with your comments or questions below.

Sources