What Do People Mean When They Talk About the School-to-Prison Pipeline?

What Do People Mean When They Talk About the School-to-Prison Pipeline?

For decades, many researchers who study the public education system have discussed the impact of the “school-to-prison pipeline”: escalating punishments, primarily in “high-poverty, high-minority schools,” intended to deter unwanted student behaviors leading to missed class time, a lost sense of belonging within the school, and often a failure to complete a high school diploma.1 These punishments include in- and out-of-school suspension, expulsion, and in some cases corporal (physical) punishment and even arrest.

Studies have shown that harsh and unforgiving school punishments—like “zero-tolerance” policies for subjective behaviors such as “willful defiance”—directly link to reduced likelihood of graduation, which correlates significantly with a higher likelihood of incarceration.2 A comprehensive survey of these studies ”tied exclusionary practices to a host of negative outcomes including lower levels of attendance, self-esteem, academic performance, and graduation as well as higher levels of anxiety, dropout, delinquency, victimization, and arrest.”3

This link between exclusionary discipline—disciplinary practices that isolate a student or remove them from school entirely—and incarceration disproportionately impacts people of color, especially Black men:

“Many studies show if a student is suspended at a younger grade, they are more likely to not finish school … they’re pushed out of school, and they’re more likely to end up in the criminal justice system. If you are a Black man in this country without a high school degree, your chances of ending up in prison at some point in your life are two-thirds. So, two-thirds of all Black men without a high school degree will be in prison at some point in their lives, one-third at any one time.”4

LISTEN: “The Movement to Dismantle the School-to-Prison Pipeline,” from “Have You Heard?”

For nearly half a century, historians of the criminal-legal system have noted that prisons and schools share troublingly similar disciplinary practices.5 These similarities were clearly evident to rapper Meek Mill, who reports getting disciplined in school for subjective behaviors like “acting up,” which eventually led to his dropping out. But he noticed another unsettling similarity between the education and incarceration systems when he walked into prison for the first time:

“I was put in disciplinary schools. It was like a jail. You get strip-searched before you go in, fingerprinted every day. … In other words, it was early conditioning for what everybody assumed your future was going to be. When I finally went to jail, I already knew everybody. Everybody I went to school with was in the jail.”6

For researchers and policymakers who focus on the school-to-prison pipeline, Mill’s experience is an example of how it “forms a key part of a larger system of criminalization and mass incarceration”—a young person experiences harsh penalties for minor infractions, alienating them from the school community and reinforcing an expectation of future incarceration; leaves school without graduating, in part due to the disciplinary approach and low self-worth; and ends up incarcerated after getting involved in crime.7

READ: “Exploring the School-to-Prison Pipeline: How School Suspensions Influence Incarceration During Young Adulthood,” from the Academy of Criminal Justice Sciences

Many schools themselves have some of the markings of prisons, with armed police officers stationed on campus. Morgan Craven, who serves as national director of policy, advocacy, and community engagement at the Intercultural Development Research Association, points out, “Millions of children who attend public schools in this country attend schools where there are police officers in their schools but there’s not a single full-time counselor or social worker.”8

This trend of funding in-school police officers but not counselors or social workers also has a racial component: Warren reports that a “quarter-million [students] are referred to police officers in schools every year; over 60,000 are arrested every year; Black students are three times as likely as white students to be arrested in school.”9 The Advancement Project’s extensive review of the research on student behaviors concludes that this racial disparity is not due to more disruptive behaviors by students of color:

“Although students of color do not misbehave more than white students, they are disproportionately policed in schools: nationally, Black and Latinx youth made up over 58% of school-based arrests while representing only 40% of public school enrollment, and Black and Brown students were more likely to attend schools that employed school resource officers (SROs), but not school counselors.”10

The connection between lower educational attainment and higher likelihood to enter the criminal-legal system has been long established, and it is a significant contributor to the rise in incarceration in the United States over the past several decades.11 In Part 2 of this series, we will look at the debates around mass incarceration and the question of whether decarceration—intentionally reducing the prison population—should be a priority, and if so, whether it can be done without creating more crime.

Discussion Questions

- What, if anything, have you heard or learned about the “school-to-prison pipeline” in the past?

- How, if at all, does this issue show up in your community?

- Do you think that exclusionary discipline practices like suspension and expulsion should be discontinued? Why or why not?

- Who should decide how best to discipline students? Elected lawmakers, youth psychology and development experts, teachers and school administrators, parents, or others?

- What are other approaches to maintaining order in schools that don’t include harsh punishments like “zero-tolerance” policies?

- How high a priority is the school-prison-pipeline issue for you?

How to Get Involved

Related Posts

- What Do “Defund the Police” and “Police Abolition” Mean? And What Do They Not Mean?

- Criminal Justice Reform: The First Step Act

- Should Public College Be Free?

- The Debate Over School Resource Officers and the #CounselorsNotCops Campaign

As always, we encourage you to join the discussion with your comments or questions below.

Sources

Featured Image Credit: Anastasya Eliseeva

[1] Wald, Johanna, and Daniel J. Losen. “Defining and Redirecting a School-to-Prison Pipeline.” New Directions for Youth Development. No. 99. Fall 2003. https://media.wiley.com/product_data/excerpt/74/07879722/0787972274.pdf

[2] Warren, Mark. Willful Defiance: The Movement to Dismantle the School-to-Prison Pipeline. Oxford University Press. 2022.

[3] Hemez, Paul, John J. Brent, and Thomas J. Mowen. “Exploring the School-to-Prison Pipeline: How School Suspensions Influence Incarceration During Young Adulthood.” Academy of Criminal Justice Sciences. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice. Vol. 18, Issue 3. 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8277150/

[4] Warren, Mark. Interview Conducted by Jennifer Berkshire. “Have You Heard?” https://open.spotify.com/episode/3pUryzGHAmEdjEOdJnCYX5?si=vkeQNPnCQm6m_c5OMQQC2Q]

[5] Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. 1975 (Gallimard, in French). 1977 (Pantheon Books, in English).

[6] Mill, Meek. Interview Conducted by Nikole Hannah-Jones for New York Times Magazine. “The 25 Songs that Matter Right Now.” 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/03/07/magazine/top-songs.html?mtrref=www.google.com&assetType=REGIWALL#/meek-mill

[7] Warren, Mark. Willful Defiance.

[8] Craven, Morgan. Interview Conducted by Dr. Terrance L Green for “Racially Just Schools.” 2022. https://open.spotify.com/episode/5852e3hLzzBjuSSeynhqc5?si=FqiwjmKASe2fB5gmJzvDgQ

[9] Warren, Mark. “Have You Heard?”

[10] Advancement Project Alliance for Educational Justice, Dignity in Schools Campaign, NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. “Police in Schools Are Not the Answer to School Shootings.” Originally Released Jan. 2013. Rereleased Mar. 2018.

[11] Bureau of Justice Statistics. “Correctional Populations Report Lower Educational Attainment than Those in the General Population. An Estimated 40% of State Prison Inmates, 27% of Federal Inmates, 47% of Inmates in Local Jails, and 31% of Those Serving Probation Sentences Had Not Completed High School or its Equivalent While about 18% of the General Population Failed to Attain High School Graduation.” Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report: “Education and Correctional Populations.” 2003.

On April 15, fighting broke out in Sudan between the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF), the country’s national army, and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a paramilitary group. The RSF is the largest paramilitary group in Africa, created in 2013 out of the Janjaweed militias that have been accused of war crimes and genocide in Darfur, a region in western Sudan, in the early 2000s.1 The conflict has displaced almost 1.1 million people, both inside Sudan and into neighboring countries. It is estimated that between 700 and 1,000 people have been killed and at least 5,287 have been injured.2 Experts say that over half of the population is in need of humanitarian aid after widespread power outages left civilians without access to water and food.3

On April 15, fighting broke out in Sudan between the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF), the country’s national army, and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a paramilitary group. The RSF is the largest paramilitary group in Africa, created in 2013 out of the Janjaweed militias that have been accused of war crimes and genocide in Darfur, a region in western Sudan, in the early 2000s.1 The conflict has displaced almost 1.1 million people, both inside Sudan and into neighboring countries. It is estimated that between 700 and 1,000 people have been killed and at least 5,287 have been injured.2 Experts say that over half of the population is in need of humanitarian aid after widespread power outages left civilians without access to water and food.3

The United States lacks public restrooms. It’s a problem you might only notice when you need to go. Those with chronic conditions such as gastrointestinal disorders, parents with young kids, and older Americans with weaker bladders may be most affected by this shortage, though anyone who just drank a large iced coffee can find themselves in need of—and struggling to find—a bathroom.

The United States lacks public restrooms. It’s a problem you might only notice when you need to go. Those with chronic conditions such as gastrointestinal disorders, parents with young kids, and older Americans with weaker bladders may be most affected by this shortage, though anyone who just drank a large iced coffee can find themselves in need of—and struggling to find—a bathroom.

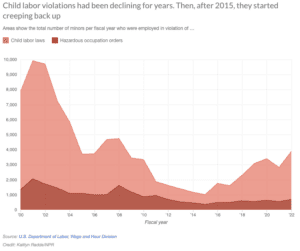

On February 27, two days after the New York Times report, President Joe Biden’s administration unveiled several policies that will be implemented to address the nearly 70 percent rise in child labor violations that has taken place from 2018-2022.11 The plan includes the creation of a new task force, targeting industries that have a history of violations, and advocating for heavier penalties and more funding for oversight.12 Congressional Democrats largely support the White House proposal. Republicans, meanwhile, say the Department of Health and Human Services is to blame for the child labor crisis because the Biden administration has loosened regulations regarding the support of migrant children.13 One third of migrant children who have been recorded by HHS now cannot be reached by government officials.14

On February 27, two days after the New York Times report, President Joe Biden’s administration unveiled several policies that will be implemented to address the nearly 70 percent rise in child labor violations that has taken place from 2018-2022.11 The plan includes the creation of a new task force, targeting industries that have a history of violations, and advocating for heavier penalties and more funding for oversight.12 Congressional Democrats largely support the White House proposal. Republicans, meanwhile, say the Department of Health and Human Services is to blame for the child labor crisis because the Biden administration has loosened regulations regarding the support of migrant children.13 One third of migrant children who have been recorded by HHS now cannot be reached by government officials.14 On February 18, the Carter Center released a statement saying that former President Jimmy Carter had opted to spend “his remaining time at home” following a number of hospital stays and declining health.1 News of the 98-year-old former president’s condition has brought an outpouring of support and renewed attention to his life and legacy as the 39th president of the United States. President Carter’s “Crisis of Confidence” speech is perhaps his most famous, and its words are still relevant for our country today.2

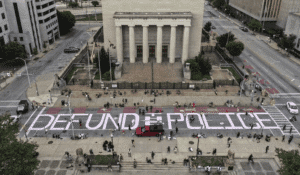

On February 18, the Carter Center released a statement saying that former President Jimmy Carter had opted to spend “his remaining time at home” following a number of hospital stays and declining health.1 News of the 98-year-old former president’s condition has brought an outpouring of support and renewed attention to his life and legacy as the 39th president of the United States. President Carter’s “Crisis of Confidence” speech is perhaps his most famous, and its words are still relevant for our country today.2 Following the 2020 murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin, a call by activists to “defund the police” achieved national attention. Supporters of defunding the police have argued that—at least some of—the billions of dollars spent on policing each year could be better used by investing in educational, recreational, and mental health programs, among others, in an effort to reduce crime and increase community well-being more generally. With the release of footage showing multiple officers pepper-spraying, kicking, and punching Tyre Nichols—leading to his death three days later—questions of whether and how to reduce police budgets have been brought back into the national conversation.1

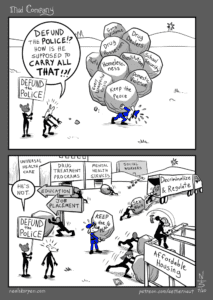

Following the 2020 murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin, a call by activists to “defund the police” achieved national attention. Supporters of defunding the police have argued that—at least some of—the billions of dollars spent on policing each year could be better used by investing in educational, recreational, and mental health programs, among others, in an effort to reduce crime and increase community well-being more generally. With the release of footage showing multiple officers pepper-spraying, kicking, and punching Tyre Nichols—leading to his death three days later—questions of whether and how to reduce police budgets have been brought back into the national conversation.1 This is what many activists mean when they call for the police to be defunded. Reduce the number of responsibilities we ask of the police, decrease police budgets to match the reduced size of the police force, and use the diverted funds to invest in programs and staff who are trained to address mental health crises, struggling schools, and other social issues.

This is what many activists mean when they call for the police to be defunded. Reduce the number of responsibilities we ask of the police, decrease police budgets to match the reduced size of the police force, and use the diverted funds to invest in programs and staff who are trained to address mental health crises, struggling schools, and other social issues.